The Dred Scott Case

|

| Dred Scott |

Dred Scott was born a slave in Virginia in about 1800. In 1830 he was taken to St Louis and sold to an army surgeon, who took him to Illinois, then to Wisconsin Territory (later Minnesota) and finally returned him to St Louis in 1842. His master died in 1843 and in 1846 Scott filed a suit in the Missouri courts claiming that residence in Illinois and the Wisconsin Territory made him free. A jury decided in his favour but the state Supreme Court decided

against him. The case of Scott v. Sandford finally came to the Supreme Court. On 6 March 1857 the Court delivered its decision. Speaking for his colleagues, the majority of whom were from the South, Chief Justice Roger B. Taney of Maryland argued that Scott had no legal standing because he lacked citizenship. At the time of the Constitution, he stated, blacks

On 16 June at what was then the State Capitol at Springfield, he delivered the speech that would launch his campaign:

He then challenged Douglas to a series of debates. These debates took place in seven towns in Illinois from 21 August to 15 October 1858 and drew large crowds.

In the first debate, held at Ottawa, Lincoln showed that though he hated slavery, he was no believer in racial equality. (He was a man of his times.)

In the same Senate campaign, as he fought to keep his New York seat, William H. Seward delivered a speech on 25 October that became notorious.

supporters. On 16 October 1859 he crossed the Potomac River into Virginia with about twenty men, including five blacks. That night he occupied the federal arsenal in Harper’s Ferry, Virginia. His plan was to arm the slaves that he assumed would flock to his cause, and set off a series of slave insurrections in the South. He took the arsenal by surprise and then took refuge in the fire-engine house until he was surrounded by militiamen and townspeople. That night Lieutenant-Colonel Robert E. Lee of the US cavalry arrived with his aid, Lieutenant J. E. B. ('Jeb') Stuart and a force of marines. On the following morning (18 October) Stuart and his troops broke down the barricaded doors. Brown was wounded. His men had killed four people in the raid and of his own force ten died, including two of his sons.

Brown was taken to Charlestown, Virginia (later West Virginia), and tried for treason and conspiracy to incite insurrection. He was convicted on 31 October and hanged on 2 December. On his way to the gallows, he handed his tailor a note:

The cult of John Brown acquired its hymn with ‘John Brown’s Body’.

By far the most important consequence of the raid was that southerners refused to distinguish between Brown and the Republican Party, even though the party was to denounce the raid in its 1860 platform. The South’s defence of slavery became ever more extreme. The Atlanta Confederacy declared:

The real southern moderates, mostly former Whigs, reorganised into the Constitutional Union Party and nominated John Bell of Tennessee.

The election was now for the Republicans to lose. The nomination at Chicago was a contest between Lincoln and William H. Seward, but Seward was seen as dangerously extreme on the slavery question and Lincoln as the moderate, with the advantage of coming from a key section of the country, the North-West.

A year previously Lincoln had expressed his doubts about his fitness to be president. In a letter to the editor of the Rock Island Register he had written ‘I must in candor say I do not think I am fit for the presidency.’ Yet in the following months he made speaking tours urging abolition of slavery in the territories.

Of the four candidates, not one generated a national following. The campaign became a choice between Lincoln and Douglas in the North, Breckenridge and Bell in the South. Douglas tried heroically to win votes in the South in order to save the Union, but his campaign was doomed. By midnight of 6 November Lincoln’s victory was clear. He had taken the key states of Pennsylvania and Indiana. He had only 39 per cent of the popular vote but a clear majority of 180 votes in the Electoral College. However, he had not won a single state in the South and when the news of his election reached Charleston, the process of secession was immediately set going.

With war seemingly imminent the federal government had lost control of all its instillations in Charleston except Fort Sumter, a massive brick and concrete fortress, forty feet high on an island in the harbour. Within days after South Carolina’s secession, Major Robert Anderson moved his seventy-three soldiers from Fort Moultrie to Fort Sumter.

By 1 February Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas had declared themselves out of the Union. On 7 February at a conference at Montgomery, Alabama, a convention confederation of the seven states adopted a provisional constitution for the Confederate States of America. On 18 February Jefferson Davis was elected as president, with Alexander Stephens of Georgia as vice-president.

According to the US constitution, Lincoln was to take place in March. This meant that the outgoing president, Buchanan, presided helplessly as the country moved to civil war. Lincoln too, was inactive during this period, unwilling to believe that the secessionists were truly in earnest. The result was a period of drift. However Buchanan seemed about to act decisively when, egged on by his much more decisive Attorney-General, he despatched a steamer with reinforcements and provisions to the Federal garrison at Fort Sumter, a sea fort located in Charleston harbour. However, batteries from Charleston drove the steamer away. This was an act of war but Buchanan chose to ignore the challenge.

On 4 March Lincoln was inaugurated. In his speech he offered to write a guarantee of slavery into the Constitution, but he stuck to his refusal to allow the extension of slavery, and he refused to recognise the right to secede or the independence of the Confederacy.

With Lincoln’s proclamation four more states were swept into the Confederacy. Virginia seceded on 17 April and the Confederate Congress then chose Richmond as its capital. (The government moved there in June.) Arkansas followed on 6 May, Tennessee on 7 May and North Carolina on 20 May. But of the other slave states, Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri remained in the Union.

On 4 April Lincoln decided to send a supply ship (not a war ship) to provision Fort Sumter. On 9 April Davis and his cabinet in Montgomery, Alabama, decided against permitting Lincoln to resupply the Fort.

At 4.30 a.m. on 12 April General Pierre G. T. Beauregard began to bombard Fort Sumter. After more than thirty hours the fort fell to the Confederacy.

On 15 April, carefully avoiding the word war, Lincoln declared a national insurrection and called for 75,000 volunteers to recapture federal forts, defend Washington and protect the Union.

The New York lawyer, George Templeton Strong wrote:

Mary Chesnut of South Carolina wrote:

|

| Chief Justice Taney |

had for more than a century been regarded as …so far inferior that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.Very controversially he also ruled that the Missouri Compromise was unconstitutional since it deprived citizens of their property in slaves. This meant that Congress had no power to exclude slavery from a territory. As the Missouri Compromise was dead anyway, this was a pointless provocation. The South was delighted, but the North was now convinced that the Supreme Court had been subverted by a slave conspiracy.

The Panic of 1857

In August 1857 America experienced a financial crisis brought about by a reduction in the demand for grain following the end of the Crimean War and the failure of an insurance company. The North suffered badly but the South was unaffected. The 1850s were the boom years of the ante-bellum period, as cotton growing became more profitable and the plantation owners built themselves large mansions. This made the South confident that it could ride out any storm. On 4 March 1858 the planter and Senator James Henry Hammond of South Carolina declared in a speech to the Senate:You dare not make war on cotton – no power on earth dares make war upon it. Cotton is King.

The Lincoln-Douglas debates

In 1858 Stephen Douglas faced re-election to the Senate. Many Democrats saw him as their saviour, a man with support from both North and South, but others opposed him because they did not see him as pro-slavery. He faced a tough fight to keep his seat, and to oppose him the Republicans chose the former single-term congressman and former Whig, Abraham Lincoln. In 1849 he had retired from active politics to cultivate his law practice in Springfield, Illinois, but the Kansas-Nebraska debate drew him back in. He was not an abolitionist or a believer in racial equality, but he abhorred slavery and opposed any extension into the new territories. In 1856 he joined the new Republican Party. In June 1858 he was selected to run against Douglas.On 16 June at what was then the State Capitol at Springfield, he delivered the speech that would launch his campaign:

A house divided against itself cannot stand. I believe this government cannot endure, permanently, half slave and half free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved — I do not expect the house to fall — but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing or all the other. Either the opponents of slavery will arrest the further spread of it, and place it where the public mind shall rest in the belief that it is in the course of ultimate extinction; or its advocates will push it forward, till it shall become lawful in all the States, old as well as new — North as well as South.

He then challenged Douglas to a series of debates. These debates took place in seven towns in Illinois from 21 August to 15 October 1858 and drew large crowds.

In the first debate, held at Ottawa, Lincoln showed that though he hated slavery, he was no believer in racial equality. (He was a man of his times.)

I have no purpose to introduce political and social equality between the white and the black races. There is a physical difference between the two which, in my judgment, will probably forever forbid their living together upon the footing of perfect equality; and inasmuch as it becomes a necessity that there must be a difference, I, as well as Judge Douglas, am in favour of the race to which I belong having the superior position. I have never said anything to the contrary, but I hold that, notwithstanding all this, there is no reason in the world why the negro is not entitled to all the natural rights enumerated in the Declaration of Independence, —the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. I hold that he is as much entitled to these as the white man. I agree with Judge Douglas he is not my equal in many respects, —certainly not in colour, perhaps not in moral or intellectual endowment. But in the right to eat the bread, without the leave of anybody else, which his own hand earns, he is my equal, and the equal of Judge Douglas, and the equal of every living man.When Douglas defended the Kansas-Nebraska Act, Lincoln attacked it as 'squatter sovereignty'. Though the debates made Lincoln a national figure, Douglas won the election for the Senate. However, the Republicans did well in the state and Congressional elections and it was clear that it would not take them much to win the presidential election that was due in 1860.

‘An irrepressible conflict’

|

| William H. Seward New York Senator and fervent abolitionist |

This was making a similar argument to the one that Lincoln had made in his ‘house divided’ speech but in a far more inflammatory fashion. It harmed Seward politically, making him seem a dangerous extremist.

Shall I tell you what this collision means? They who think that it is accidental, unnecessary, the work of interested or fanatical agitators, and therefore ephemeral, mistake the case altogether. It is an irrepressible conflict between opposing and enduring forces, and it means that the United States must and will, sooner or later, become either entirely a slave-holding nation or entirely a free-labor nation. Either the cotton and rice-fields of South Carolina and the sugar plantations of Louisiana will ultimately be tilled by free labor, and Charleston and New Orleans become marts for legitimate merchandise alone, or else the rye-fields and wheat-fields of Massachusetts and New York must again be surrendered by their farmers to slave culture and to the production of slaves, and Boston and New York become once more markets for trade in the bodies and souls of men.

John Brown’s raid

Since the Pottawatomie Massacre in 1856 John Brown had lived a furtive existence in New England raising funds and arms from |

| John Brown (1859) |

|

| The fire-engine house where Brown and his followers took refuge. |

Brown was taken to Charlestown, Virginia (later West Virginia), and tried for treason and conspiracy to incite insurrection. He was convicted on 31 October and hanged on 2 December. On his way to the gallows, he handed his tailor a note:

I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood.To Ralph Waldo Emerson, Brown was ‘the new saint’, to Louisa M. Alcott ‘Saint John the Just’. However, Lincoln thought he was justly hanged. Just before the execution, the poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote, 'They are leading old John Brown to execution. This is sowing the wind to reap the whirlwind, which will soon come.'

The cult of John Brown acquired its hymn with ‘John Brown’s Body’.

By far the most important consequence of the raid was that southerners refused to distinguish between Brown and the Republican Party, even though the party was to denounce the raid in its 1860 platform. The South’s defence of slavery became ever more extreme. The Atlanta Confederacy declared:

We regard every man in our midst an enemy to the institutions of the South who does not boldly declare that he believes African slavery to be a social, moral, and political blessing.The historian Hugh Brogan writes

John Brown’s raid thus marks the point of no return: it began the uncoiling of a terrible chain of events leading to rebellion and war. (The Penguin History of the USA, (1999), p. 309)

The election of 1860

In April 1860 the Democratic Convention met in Charleston, South Carolina, to choose a candidate. The Northerners wanted to nominate Douglas but the Southerners refused to accept him. The convention broke up. One fragment reassembled at Baltimore on 18 June and nominated Douglas as the official candidate. The others nominated the Vice-President, John C. Breckinridge of Kentucky, who was a moderate by southern standards. The southern moderates formed themselves into the Constitutional Union Party and nominated John Bell of Tennessee. The once national party was now hopelessly fragmented.The real southern moderates, mostly former Whigs, reorganised into the Constitutional Union Party and nominated John Bell of Tennessee.

The election was now for the Republicans to lose. The nomination at Chicago was a contest between Lincoln and William H. Seward, but Seward was seen as dangerously extreme on the slavery question and Lincoln as the moderate, with the advantage of coming from a key section of the country, the North-West.

A year previously Lincoln had expressed his doubts about his fitness to be president. In a letter to the editor of the Rock Island Register he had written ‘I must in candor say I do not think I am fit for the presidency.’ Yet in the following months he made speaking tours urging abolition of slavery in the territories.

|

| Abraham Lincoln the Republican nominee |

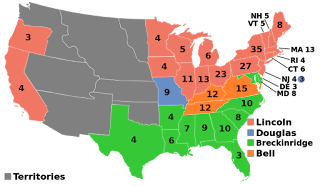

Of the four candidates, not one generated a national following. The campaign became a choice between Lincoln and Douglas in the North, Breckenridge and Bell in the South. Douglas tried heroically to win votes in the South in order to save the Union, but his campaign was doomed. By midnight of 6 November Lincoln’s victory was clear. He had taken the key states of Pennsylvania and Indiana. He had only 39 per cent of the popular vote but a clear majority of 180 votes in the Electoral College. However, he had not won a single state in the South and when the news of his election reached Charleston, the process of secession was immediately set going.

|

| Results of the 1860 election |

The secession of the South

On 20 December a convention met Charleston and after twenty-two minutes unanimously endorsed an Ordinance of Secession:We the people of South Carolina, in convention assembled, do declare and ordain…that the union now subsisting between South Carolina and other states under the name of the United States of America is hereby dissolved.

With war seemingly imminent the federal government had lost control of all its instillations in Charleston except Fort Sumter, a massive brick and concrete fortress, forty feet high on an island in the harbour. Within days after South Carolina’s secession, Major Robert Anderson moved his seventy-three soldiers from Fort Moultrie to Fort Sumter.

By 1 February Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas had declared themselves out of the Union. On 7 February at a conference at Montgomery, Alabama, a convention confederation of the seven states adopted a provisional constitution for the Confederate States of America. On 18 February Jefferson Davis was elected as president, with Alexander Stephens of Georgia as vice-president.

According to the US constitution, Lincoln was to take place in March. This meant that the outgoing president, Buchanan, presided helplessly as the country moved to civil war. Lincoln too, was inactive during this period, unwilling to believe that the secessionists were truly in earnest. The result was a period of drift. However Buchanan seemed about to act decisively when, egged on by his much more decisive Attorney-General, he despatched a steamer with reinforcements and provisions to the Federal garrison at Fort Sumter, a sea fort located in Charleston harbour. However, batteries from Charleston drove the steamer away. This was an act of war but Buchanan chose to ignore the challenge.

|

| Aerial view of Fort Sumter, now a national monument |

On 4 March Lincoln was inaugurated. In his speech he offered to write a guarantee of slavery into the Constitution, but he stuck to his refusal to allow the extension of slavery, and he refused to recognise the right to secede or the independence of the Confederacy.

With Lincoln’s proclamation four more states were swept into the Confederacy. Virginia seceded on 17 April and the Confederate Congress then chose Richmond as its capital. (The government moved there in June.) Arkansas followed on 6 May, Tennessee on 7 May and North Carolina on 20 May. But of the other slave states, Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri remained in the Union.

On 4 April Lincoln decided to send a supply ship (not a war ship) to provision Fort Sumter. On 9 April Davis and his cabinet in Montgomery, Alabama, decided against permitting Lincoln to resupply the Fort.

At 4.30 a.m. on 12 April General Pierre G. T. Beauregard began to bombard Fort Sumter. After more than thirty hours the fort fell to the Confederacy.

|

| No-one was killed at the attack on Fort Sumter but the damage was considerable. |

The New York lawyer, George Templeton Strong wrote:

So the Civil War is inaugurated at last. God defend the right.

Mary Chesnut of South Carolina wrote:

Woe to those who began this war if they were not in bitter earnest.

No comments:

Post a Comment